2021

We all have our weak spots. One of mine is getting up in the middle of the night. However much patience I have under the best of circumstances (and I do not have the patience I should even then) I have much less patience in the middle of the night. I regularly do not rise to the occasion with grace when a child bellows in the middle of the night, “Daaadddy!”

For this I am sorry. A two-year-old can’t help that he needs to go to the bathroom at 2AM. It isn’t his fault that his siblings woke me up twice in the night already and more is probably coming. It isn’t his problem that I have to get up at 4:30AM because tomorrow is a work day and I don’t know how I am going to make it through the week because I am so tired. He is two, he can’t make it down to the bathroom by himself, and it is a great unkindness to him for me to be grumpy.

And yet I am. Often.

In the light of the morning I regularly see myself for what I am, and yet like a pig returning to the mud I am grumpy again when the middle of the night comes. I am not always outwardly grumpy. Sometimes I do make the bathroom trip without being verbally short with the little boy. But inwardly there are still the thoughts and feelings of, “I wish I didn’t have to get up. If only I could sleep through the night without interruption. I am so tired…” and so the litany of complaints goes within my mind until I get the child back into bed and collapse there myself.

The better moments are when I see beyond what I am (a grump) to the reality of what is. There are times where—in the flash of a moment—I see myself from the outside and I see things differently. One night not so long ago I was heading back upstairs from a little boy bathroom trip. Little hand in mine, we started up the stairs together. It was like so many times before where I was wishing I was still asleep in bed, and yet for that flash of a moment I saw it all differently.

I had a little boy who depends on me to take him to the bathroom in the middle of the night. The greatness of that reality caught me. No, I have two little boys who depend on me to take them to the bathroom. And soon enough a little girl will join those nightly treks. But soon enough they will all be grown and not need those nightly journeys. Soon enough they will fly away. But for now they are here, they are given to me, and they need me. And in light of that great truth, with this little hand in mine, is all I can think about really how I wish I was still asleep and didn’t need to do this?

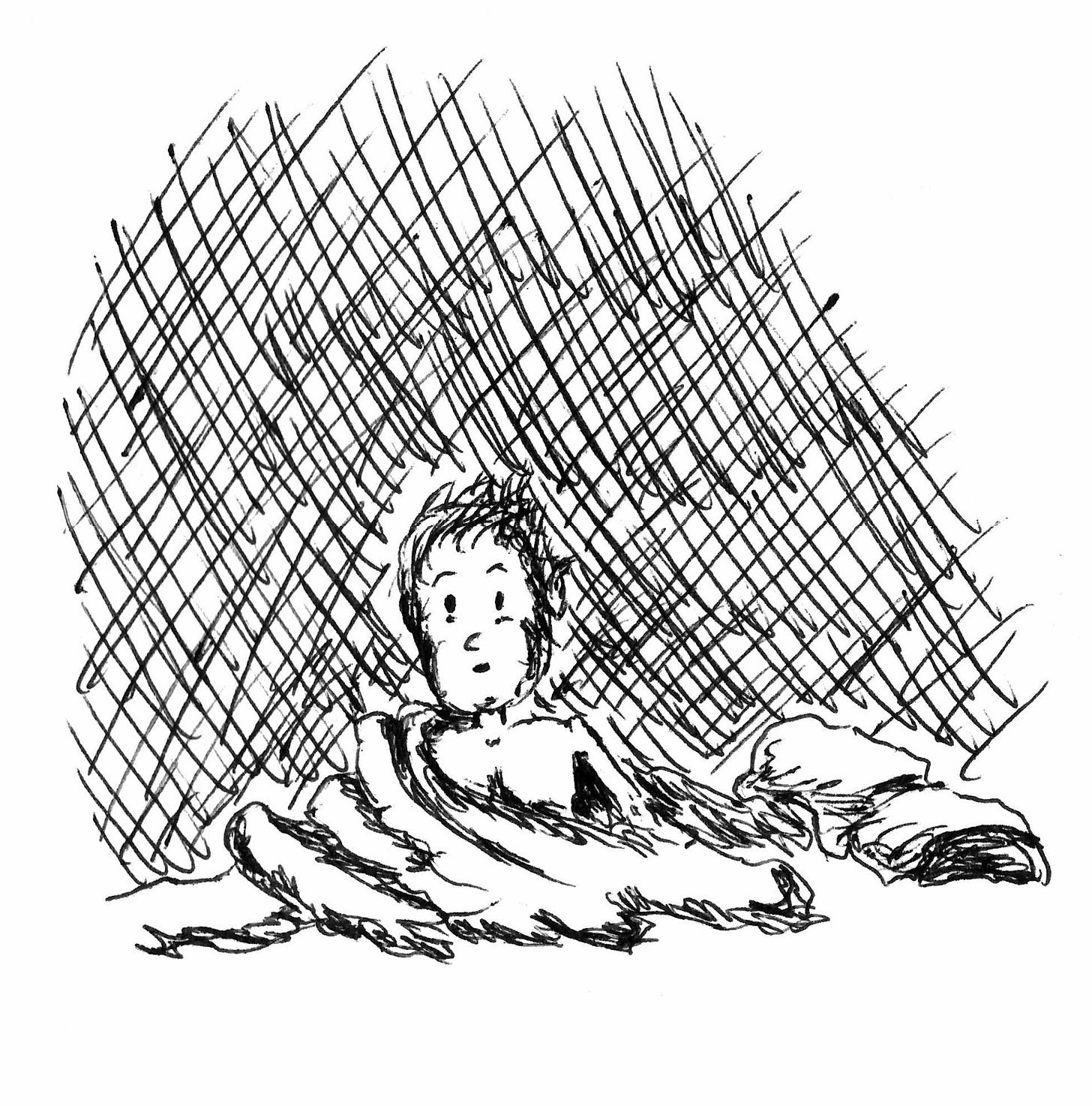

In that moment in the night I was struck by my profound ungratefulness. It is a good thing to have a little boy to take to the bathroom. A beautiful thing. Is it always easy? No. Am I terribly sleep deprived? Often. But it is a great gift to have little children to take to the bathroom in the middle of the night, and it is a thankless heart to forget the goodness because of the momentary hardness. I felt that reality in a way I too rarely do.

I went back to bed feeling my own smallness, and momentarily seeing the great goodness in my life. I wish I could say it stuck.

Ungratefulness is a hard attitude to escape, but I am grateful for those moments when I am given a better glimpse of the life I have and the goodness hiding in plain sight. May I see it more and more. And may I be changed by it.

2024

It is hard to process the loss of others in a way that makes right sense of my own life.

A few years ago a man whose blog I follow lost his young adult son. I don’t know this man in person, he is a stranger to me, nearly half way around the world. His son was in the prime of his life, about twenty, and died quite suddenly from an undiagnosed heart issue. One day he was healthy, happy, full of life and preparing to marry his sweetheart. The next day he was dead. His father went from having a son dear to him, close to him, a son whom he could look forward to having a wonderful and rich future with—to having only memories left. Memories and hurt.

I respect how this man walked through that devastation publicly. He wrote of it, but with discretion. He was honest about the hardness and hurt, but also wrote frankly about where he found hope. His blog did not become consumed with that loss, but on anniversaries or other occasions he will return and remember what happened. But it feels like I can’t read anything on his blog without thinking about what happened, and imaging his life and his loss and dwelling on it as if it was me and my boy. It gnaws at me, thinking about what it would be like to see one of my sons live twenty years and then lose him so suddenly. What would I do, what would life be like?

I feel bad that I keep thinking about this man’s loss when I read his writing. Who wants to be reduced to the tragedy of your life? And yet I find myself unable to forget his past and read his writing for what it is in the present. How am I to do that?

More recently a nurse at work was telling a story from a few years ago, during the height of COVID. In her previous job she was an ER nurse of many years and the story was about a family who lost their two-year-old son. They had been doing a family Bible study when at some point they realized the littlest was missing from the room. They searched around the house and didn’t find the boy, and then went outside looking. There they found the child, face down in the pond.

The nurse was part of the ER team who tried to revive the boy. She said they tried a long time and finally the father—standing there and watching the team trying to save his son—came unglued and the nurse had to take him outside. After trying to calm and comfort him she went in again to join the team in their efforts to save the boy, but to no avail. After more minutes of futility the nurse went back outside to try to comfort the father as she gave him the news that his little boy could not be saved.

For my fellow nurse the point of the story was how much she hated the gear they had to wear during COVID which made a barrier against being close and giving comfort to people. Listening to the story, I was wrecked thinking about the dead little boy and his broken father. It was in one sense like every other child drowning story of the thousand you will read and hear about in a lifetime, but it was particularly vivid for me—being a nurse hearing it from another nurse, imaging myself there. It made my gut feel hollow, imagining myself the father, imagining the despair and loss and self-loathing I would feel in what would seem like such a preventable accident, a small oversight that ended a life. My boy’s life.

“Thank God I don’t have a pond,” is a little thought that slips through, but in that very moment I know it is a lie. The road passes maybe fifty feet in front of the house. We impress upon the kids that nobody should go into the road, or even close to the road. And they learn, and they are good. But it takes just one moment of forgetfulness, one second of inattention when a child runs after a wayward ball—and I can see in my mind too well the image of an F-150 striking my child at forty-five miles per hour. The ball bounces harmlessly the rest of the way across the road. The little body is flung aside in a blur, broken and bloody.

I wish I could push the image out of my mind, wish it had never come, unbidden. But the reality I must face is that I can never comfort myself with the idea that at least I don’t have the danger in my life that the other family did. There is danger on every side, for all of us. Death can come sudden, in an instant, from anywhere, from where we least expect it. A heart defect, a drowning, blunt impact, and more.

It is hard to be thankful when little kids get me up in the middle of the night, and I wish it came more easily for me. But it can sometimes be a harder thing to know how to rightly live out thankfulness when feeling the fragility of all that we have. Thankfulness isn’t hanging on to it all with a throttling desperate grasp, though sometimes it can be tempting to think so. Thankfulness is holding things lightly, gratefully, in spite of all the losses that will come, somehow even embracing those yet-to-come losses with a gladness in the goodness of the moment of now and the goodness yet to come.

But I’m not sure I know how to do that.